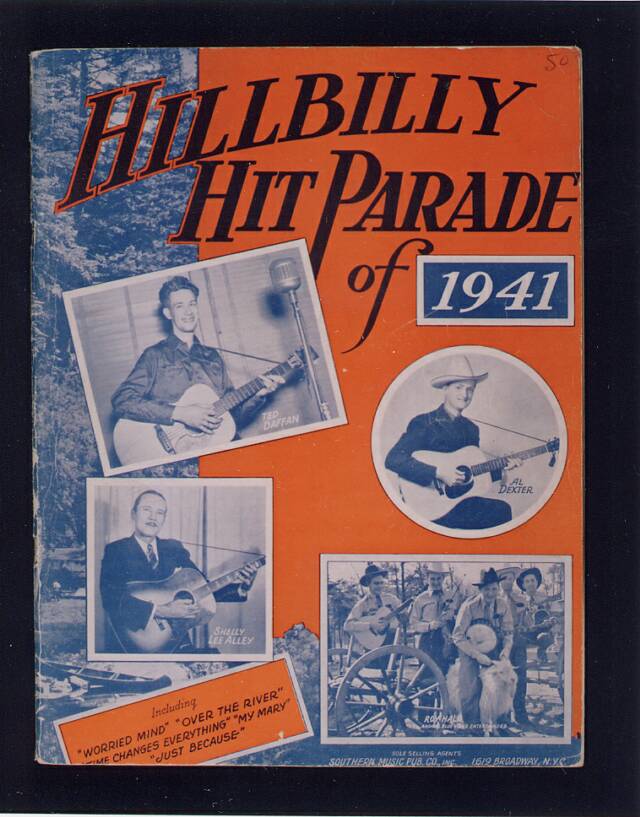

In 1894, Abraham's grandson, Shelly, was born near Alleyton, Texas. Shelly's story is best described by the following article that was written by Kevin Reed Coffey for The Journal of Country Music, Volume No. 17:1;

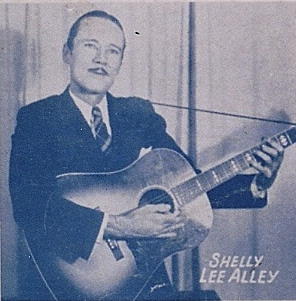

Shelly Lee Alley is a puzzle of contradictions and half-fulfilled promise. As the writer of Jimmie Rodgers' classic, "Travellin' Blues", as an early exponent of western swing, and as a star of early Texas radio, he looms as something more than a footnote in country music history. But how much more? That question goes to the heart of his frustrating career.

A pop musician, songwriter, and bandleader who veered toward hillbilly music at mid-career, but who seems not entirely to have come to terms with the implications of that move, Alley elicits both veneration and disappointment from those familiar with his music. His recorded blues and hokum hold up well today, fine examples of free-wheeling, good-time dance music of the Depression years, while his ballads-on record, at least-fare far less well. Alley himself retained little affection for the risque' blues and stomps, dying frustrated that what he felt were his best songs were left either unrecorded or unreleased.

I'd like to take my broken dreams

And lay them tenderly

Upon a lonely stretch of sand

Somewhere beside the sea

---Shelly Lee Alley,

"Broken Dreams"

If I buy her pretty silk things

I wont buy them all at one time

She'll get rambling on her brain

And some triflin' man on her mind

---Shelly Lee Alley,

"New Mean Mama Blues"

What was recorded and released is a bizarre mix, its wide divergences captured pointedly in the lyrics-from one of his strongest ballads and one of his most typical off-color blues-quoted above. Commercial and artistic considerations often clashed; his songwriting was characterized on one hand by a cloying sentimentality fostered in the more innocent times before the First World War and on the other by a cynical, Jazz Age hedonism unrelentingly preoccupied with sex and beer joint carousing.

As startling as the stylistic struggles and juxtapositions in Alley's music can be, lending it both its vibrancy and its maddening unevenness, they are ultimately blurred by the force of his unflappable personality. To him, it was all just music---his music---and making music was Shelly Lee Alley's life-long obsession. "He thrived on it," says his son, Shelly Lee Alley Jr. "You could read his mind with no problem because music was all he ever thought about."

Shelly Alley possessed boundless confidence in his musical ability and vision; and if that confidence is not necessarily justified by his legacy, it is also true that that legacy was compromised by commercial dictates, by a rapidly changing musical climate, and hampered by alcohol abuse. He was resilient and highly adaptive and though he undeniably remains a man who should have achieved more than he did, his stubborn attempts to forge a career of his obsession were nevertheless oddly compelling---comic, tragic and sometimes triumphant---touching artists from Rodgers to Harry Choates, from Jimmie Davis to Ted Daffan, even George Jones and Merle Haggard.

Shelly Lee Alley was born July 6, 1894, near Alleyton, Colorado County, Texas, where he also spent his formative years. He claimed to have written the first of his several hundred compositions at age six. In his teens, he somewhere learned to read and write music, and by the time he was serving in a medical unit at San Antonio during World War I he had learned to play violin, cornet, and saxophone. His influences were diverse.

In later years, he would regale his family with tales of tent shows, small-time vaudeville, of being taken by his father to Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. He spoke of Caruso, Al Jolson, Paul Whiteman; and although his early professional career was spent playing popular dance music, it seems safe to assume from his decidedly rustic fiddling on recordings that he was also affected by the folk musics of the region.

At some point during his wartime tenure at San Antonio, Alley became leader of the base orchestra and at war's end he headed for Dallas, determined to make it big in music. By 1920, he was gaining recognition both as a bandleader and a songwriter. The Dallas Morning News reported that year that "the coming musical season promises to find many of the song "hits" coming out of Dallas" and that "the last but by no means least of such songwriters to gain sweeping popularity is Shelly Lee Alley...leader of the 'Star Orchestra'..." Alley was soon running several orchestras simultaneously, and when commercial radio came to Dallas in 1922 he was among the first to take advantage of the new medium. He later claimed to have broadcast the first program over KRLD and he was definitely appearing regularly on the station within a few months of its inauguration. According to The Dallas Morning News, the Footwarmers, a hot jazz combo drawn from Alley's orchestra, created a sensation far beyond Texas when they first broadcast in January 1923. The Footwarmers performed jazz standards like "Sister Kate," but throughout his career Alley preferred to tap his own considerable flow of originals. It's not surprising then that he soon took his full band, the Dixie Serenaders, to KRLD's studios, augmented with (said the Morning News) "three singers presenting compositions by Mr. Alley," among them "Those Mean Mama Blues", "Love Dreams," and "Dear Little You." The presence of a low-down blues amid tender love songs indicates that the man whom the Morning News had touted in 1920 as a leading writer of "the sweet old-fashioned ballad" was beginning to respond to other more prurient influences and that the dichotomy that would characterize his repertoire was already crystallizing.

By the mid-twenties, Alley was a fixture on Dallas-Ft. Worth radio and enjoyed a summer residence at the Oakdale Casino in Glen Rose. Okeh Records contacted him regarding a recording contract in 1927, but apparently nothing materialized. In addition to leading three orchestras, he also became a partner in a Dallas music store. The grind proved too much, however, as he explained to a hometown newswriter in 1931, "The Dr. said I must go to the country for a while, or the cemetery, one, and I've never liked the looks of a cemetery, anyhow." Whether the physical collapse resulted more from overwork or from the overindulgence's that would dog him through much of his career---or both---is unclear; regardless, Alley's marriage to Phyllis of a little over ten years ended and Shelly relocated to Ramsey where he remained there for the next several years.

The years back in Colorado County were quiet ones but would prove very important to Alley's subsequent career. "I wasn't accustomed to this early to bed and early to rise," he told the Colorado Country Citizen in 1931, "and for months when they were all in bed at 9:00PM sharp, I stayed up until two or three in the morning writing songs." After a few months R&R, Alley was playing again, with Jodie Braden's local orchestra. Later, he was involved in a music store with Braden as well, but it was one of his late-night songwriting bouts that kicked his career into high gear again. "One night I had the blues," he told the Citizen, "and what I mean to tell you I was sure enough blue, then all of a sudden a train passed. Then I decided I'll catch the very first train for Dallas and take a chance on the cemetery regardless of what my Dallas Dr. told me. That was the night I wrote the "Travellin' Blues".

It's unclear when Alley first met Jimmie Rodgers, but the two were friends and Alley renewed the acquaintance when Rodgers played Eagle Lake, Texas, during a 1930 tour. Rodgers was at the height of his considerable fame and Alley, an indefatigable self-promoter, doubtless saw "Travellin' Blues" as an ideal vehicle for the Singing Brakeman:

I'm going away

I'm leaving today

I'm gonna bring my baby back

If them eight-wheel drivers

Don't jump the railroad track

Rodgers was understandably drawn to the song, and when he detoured from a tour to record in San Antonio in January 1931 he picked up Shelly Lee and his brother Alvin, also a fiddler, on the way. The Alley's twin fiddles backed Rodgers on "Travellin' Blues" and the recording became a considerable hit, one of Rodgers' most durable and oft-covered tunes. The Alley's fiddling gave the original recording added importance, as well. As Nolan Porterfield has pointed out, "'Travellin' Blues' brought together, in however rudimentary a fashion, the strains of several musical traditions, notably jazz-blues and those elements of popular music most directly derived from older, 'folk' roots. The particular instrumentation of the string band, highlighted by the Alley brothers' violins---the sound was not yet quite that of fiddles---caught the attention of younger musicians such as Bob Wills, the fledgling genius who was to make western swing an indelible part of American musical culture."

Though one could argue with Porterfield that the Alley's sound was absolutely that of fiddlers rather than violinists---despite his musical knowledge and experience. Alley never sounded like anything but a fiddler---the recording nevertheless broke important ground. Having a bonifide star like Jimmie Rodgers record one of his songs---a year later he would record "Gambling Bar Room Blues," Alley's spin on "St. James Infirmary"---was also a huge feather in Alley's cap, one that he would exploit effectively to the end of his career. And though he sold the rights to the song--his family would finally regain these years later---it propelled him out of Colorado County and back into a full-time musical career. It also eased Shelly into the realm of country music, for despite Rodgers eclectic approach and often adventurous instrumentation, he was nevertheless generally considered "only" a hillbilly singer. Whether owing more to commercial considerations or because he felt he had found a more suitable sphere for his talents, Alley sought a similar niche.

Musically, the crossover was neither a stretch nor a pretense. Texas country music of the era was so heavily influenced by jazz and popular music that Alley probably found it unnecessary to alter his approach to any appreciable extent. He had concentrated on violin from at least the early twenties and does not seem to have been straightjacketed by any adherence to formal technique---he was, in short, already a fiddler. The only major difference in the bands he led before and after seems to be the dominance of string instruments in the latter, and the musicians, especially by the late thirties when western swing began to coalesce into a distinct style, were likely playing similar music---dance music with heavy doses of jazz.

Moreover, country music's historic tendency to embrace elements of pop music that are perhaps no longer commercially viable in the mainstream, combined with Alley's somewhat old-fashioned sensibilities, may have made the switch inevitable, even necessary. Alley's ballads, the songs closest to his heart, were arguably too effusive, too sentimental for pop success---even the 1920 Dallas news item had characterized them as old fashioned. In country music of the thirties and forties, they were not so much so---"Broken Dreams" and a few others hold up against anything from those years, including many pop hits---though many of them still sounded dated against the sometimes more sophisticated music and lyrics of younger artists whose sensibilities were shaped a generation after his. Although Alley's correspondence reveals that he considered himself on a different plane musically from most of "these hillbillies", as he called them---despite the fact that his records were released in the same series, that he played the same venues as they, and used many of these same musicians---it seems very unlikely, in light of his limitless devotion to his music, that his motives were largely commercial. Perhaps he sensed---despite his talent, experience and considerable confidence---that his songs weren't likely to score as Tin Pan Alley pops. At any rate, the pop and jazz-tinged terrain of Texas swing offered a compromise, a sometimes uneasy middle ground, but one that held out opportunities for expression not as easily accessible in straight pop or hillbilly. It was still a compromise, however, and one wonders whether "settling" for a career in hillbilly music contributed to his alcoholic binges during these years---if perhaps drinking helped blur the line between where he found himself and where he thought he should be.

Alley's return to Dallas prompted a serious return to song plugging, and he received rejection letters during this time from artists as diverse as Bing Crosby and W. Lee O'Daniel, the latter a friend from the border radio days if not before. Nothing promising materialized, and so the opportunity to record as a member of Lummie Lewis & his Merrymakers, apparently a pick-up group that never recorded again, probably came at a critical time. Alley appears only as a vocalist on this session and sings three of his own songs: "Those Mean Mama Blues," the catchy "Sweetheart of Mine", and "Save It For Me," a piece of off-color hokum that foreshadowed things to come. The group also cut a version of "Travellin' Blues." The session provided Alley crucial access to Satherley and when he returned to Houston soon after, he did so with a recording contract in hand.

For his first session, Alley recruited a pick-up band of young Houston players corralled by guitarist Chuck Keeshan. The group included aspiring songwriter-steelguitarist Ted Daffan and hot fiddler Cliff Bruner, at twenty-two already a revered trendsetter on his instrument. Alley called his band the Alley Cats, a name resurrected from his mid-twenties tenure at KRLD (it was "Alley Kats" in those days).

The session almost didn't come off. As Daffan recalls, "Shelly...got blind drunk" prior to recording and had to be primed with coffee in a almost futile attempt to sober him. He still sounds far from sober on the released sides, but it was a strong session in its own way, especially the good-time dance music, the proceedings buoyed considerably by Bruner. From the start, Alley established patterns that would characterize his recording persona, incongruously mixing sentimental ballads like, "My Precious Darling" with often risque' blues and hokum like "Let Me Bring It To Your Door" and "Women, Women, Women". Jimmie Rodgers and the young Jimmie Davis had managed to balance such divergent aspects nicely, but Alley was not as successful---often the juxtaposition is jarring. Alley would later complain about Satherley's demands for off-color material for beer joint jukeboxes. Though Satherley requested such material from all his dance bands, none of his acts recorded nearly as many numbers like "What Size Do You Need?", "Hang Your Pretty Things By My Bed" or "She Just Wiggled Around" as Alley, leading one to wonder just how much Satherley and how much Alley himself was responsible for this frequency. Along with Buddy Jones and Hartman's Heartbreakers, Alley ranks as one of the era's chief exponents of risque' material. Fortunately, hot solos abounded, and Alley always retained plenty of humor and ingenuity in these songs, as in "I've Got the Blues #2".

After peeping through your keyhole

And watching you do your dance

I decided, baby, to give you another chance

Stylistically, the Alley Cat records are classic early western swing, with jazz solos from fiddle, piano, and sax or clarinet, and a strong dance beat. Alley played fiddle sparingly and always stuck to straight lead. His vocals ranged from apt and sharp to dreary and maudlin---an odd amalgam of Gene Austin, Jimmie Rodgers and alcohol---and on ballads, especially, they often didn't do his songs proper justice. Most of the sides the Alley Cats recorded were Alley's originals, but he seems also to have labored diligently to get the early efforts of up-and-comers like Daffen and Blue Ridge Playboys' pianist Ralph Smith on record.

While Alley had no major successes, his Vocalion releases must have sold consistently well, for Satherley continued to record him on every field trip through 1940. In those years, the Alley Cats waxed nearly seventy sides. Alley used Leon Selph's Blue Ridge Playboys for several of these sessions, and the polish of a working group gives the recordings a tightness that a pick-upband might not have had. The late Ralph Smith told Alley's stepson Clyde Brewer that Alley would take a briefcase filled with as many as seventy-five original songs when he went to a session at which he was scheduled to wax only eight to twelve sides; most of these Satherley would reject as too pop for jukeboxes, an opinion that left Shelly exasperated and much of his most promising material unrecorded or unreleased. Reed player George Ogg, an eighteen-year-old seasoned vet when he recorded with the Alley Cats in 1939, relates a telling story that typifies the major labels' attitude toward country acts---an attitude that has arguably not much altered a half-century later. After Ogg played a particularly attractive clarinet solo on "I'm Wondering Now," someone came from the recording booth and asked him please please not to do it again. "Dammit, if I'd wanted good music," he said, "I'd've hired good musicians."

Aside from his recording activity, Alley's career during these years is hard to assess. Despite his pioneering efforts in radio, he seemed either unconcerned with or unable to obtain regular exposure. A local radio writer, noting Alley's absence from the airwaves and the big crowds he was drawing despite this, mused, "Pretty good work, Shelly old boy....Someone in the business once told me that a band without an air spot wouldn't go over. All I can say is that 'he' didn't stop to think of how many followers Shelly really had." Gigs varied widely---from dingy beer joints and popular dancehalls like the Old Style Inn in Pearland to theater chain tours. Alley apparently worked mostly with pick-up bands, and musicians he used included a teenaged Cameron Hill (later a guitarist with Bob Wills and Spade Cooley) and legendary Cajun fiddler Harry Choates, who played mandolin with Alley in 1940. Guitarist-vocalist Clarence Standlee made several theater tours with the Alley Cats and recalls Alley as a master showman. "He was a hell of an emcee. He knew how to meet the public. That was a big part of it back then. Some guys didn't care---were flip with the audiences---and they didn't last long, no matter how talented they were."

These were also years of personal upheaval. The third of four marriages was over by the time the U.S. entered World War II, and Alley's drinking and carousing occasionally reached dangerous proportions. One musician who worked with him remembered that Alley's drink of choice at the time was the stomach remedy paregoric---"He had a little vial of it and drank it like it was whiskey," perhaps a habit from the prohibition days---and that at least once he was so far under that the band thought he might have drunk himself to death.

Surviving correspondence also gives the impression that Alley continued to suffer from physical breakdowns like the one that had flattened him in Dallas at the end of the twenties. For instance, his publisher Bell Music wrote in 1940 expressing concern over Alley's grave physical condition---but denying a request for a $25 advance on royalties. And in a letter dated a month later, western swing bandleader Bill Boyd wrote that he was "sure sorry to hear of your nervous breakdown and hope that there isn't anything to it..." According to Shelly Alley Jr. and Clyde Brewer, however, Shelly's illnesses were motivated mostly by commercial considerations, inspired by the public's (and by his own) somewhat romantic ideas regarding Jimmie Rodgers's tuberculosis and early death. Alley believed that serious illness would enhance his stock, would give him the same ill-fated, exotic aura. The idea obviously appealed to him from more than a commercial standpoint. "For many years he would tell people he had T.B.," laughs Clyde, "and I thought he did." Shelly Jr. says that this tendency exasperated his mother. "She'd say, 'Why in the world do you tell people that? It's a contagious disease. Don't you realize people will want to stay away from you if you tell them that?"

Alley's correspondence also documents his tireless efforts to place his songs with other artists---to hit on another "Travellin' Blues"---as well as his anger, often vented at his publisher, C.J. Heriter at Bell Music, that he was not as successful in this as he thought he should have been. Actually, he did rather well, more through his own hard work than Heriter's. Jimmy Davis recorded "I'm Wondering Now"; Bill Boyd cut a terrific arrangement of "I'll Take You Back Again"; Cliff Bruner, with Moon Mullican on vocals, did "I'll Forgive You but I Can't Forget" and "I'll Keep on Smiling." The Lightcrust Doughboys cut two sides that never saw the light of day because of the war, and banjoist Marvin Montgomery recalls that the Doughboys often performed Shelly's songs on the radio. Even big band leader Bob Crosby, Bing's brother, covered, "I'll Keep Thinking of You" in 1941.

Alley regretted having sole the rights to "Travellin' Blues," and he made sure that he hung on to his other songs. He tried to publish as many of these as possible, though ironically this policy ended up stalling his recording career. The majors spent as little as possible on their hillbilly recordings and to increase profits---among other reasons---preferred unpublished songs from their 'race' and hillbilly acts so they wouldn't have to pay the half-cent per side publisher's royalties. Alley's attempts to publish the songs he was recording, as well as his disgruntlement that he was not being allowed to record his best material, led to tension with Satherley and Columbia (which bought Brunswick-A.R.C. in 1938) that culminated in Alley's departure from the label. As he explained in a letter to R.B. Gilmore of Southern Music in 1941, "I fully agree with you about the record companies wanting unpublished songs so they will only have to pay 1/2 cent per side....In fact, that is the main reason I am not recording for Columbia anymore. Art Satherley didn't want me to get any of my songs published and he would not let me pick my songs to record. To cut a long story short, he didn't want any good songs. He has eight masters of my best songs....and now his only reason for not releasing them is that they are too popular. He doesn't want a good song or a good songwriter....He wants ignorant hillbillies that can't play a tune right, and of all things he wants them to write their own songs."

The letter reveals as much about Shelly's own inner battles---it seems clear, despite his circumstances, that he didn't remotely consider himself a "hillbilly" artist---as it does about the attitudes and practices of the record companies. (It should be noted, in fairness to Satherley, that Alley's complaints about him seem to be isolated ones. Marvin Montgomery of the Light Crust Doughboys specifically recalls that Satherley urged him to get his songs published.) It's obvious, too, despite his confidence, that Alley found it frustrating to watch younger, less schooled musicians score the considerable hits that were eluding him. He also felt taken advantage of. "I have quit helping these hillbillies," he wrote Gilmore, "because after I do all they do is go off and talk about me." This anger seems to have been fleeting and he continued to labor on behalf of colleagues like Buddy Duhon, whom he apparently championed to Satherley and who recorded two of Alley's songs for rival Bluebird in 1941. Duhon's covers probably led to Alley's own six-song session notable for the unusual prominence of Alley's fiddling and some interesting electric guitar work.

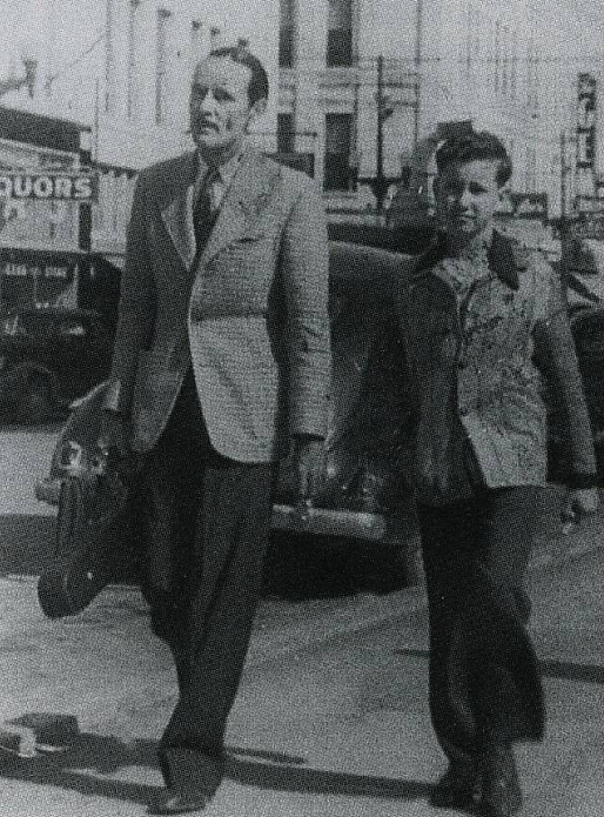

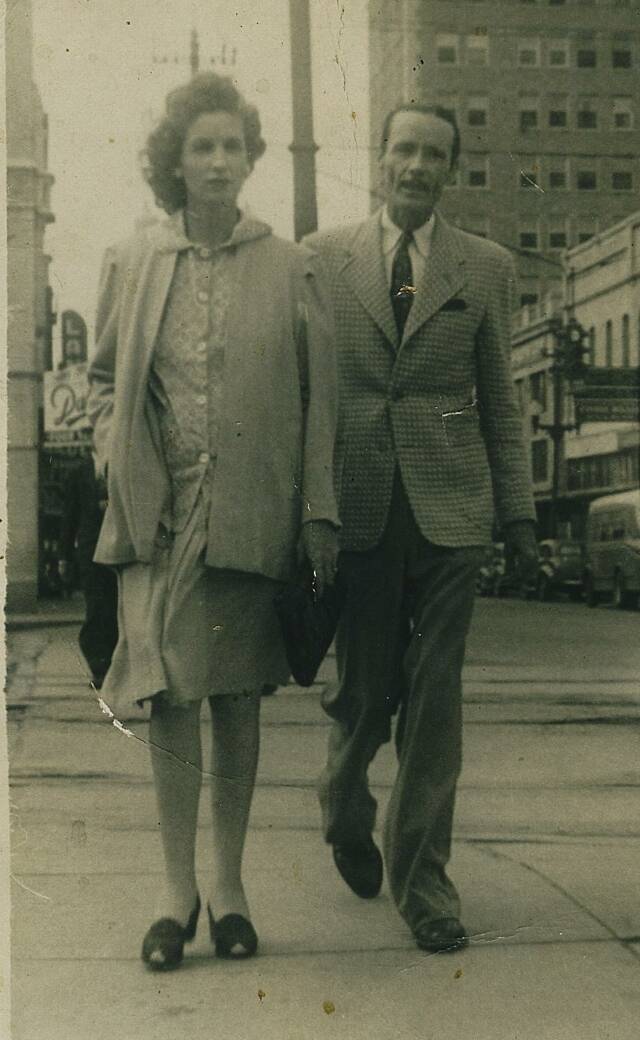

During the war, Alley relocated to Beaumont, where he began appearing with a local act, Patsy & the Buckaroos, that included thirteen-year-old Clyde Brewer on mandolin. Before long, Shelly and Clyde left to reform the Alley Cats. They secured a daily radio show on KRIC and put together pick-up bands for dances and shows. Alley also married Clyde's mother Velma, and this fourth marriage proved a lasting one. Under Velma's influence, Alley stopped drinking and became a Christian. "God and my mother," says Shelly Jr., who was born in 1945, "were the only ones who could change him."

Alley moved his family to Houston and, with Clyde as his right hand, continued to perform through 1946. He made his last record as a bandleader for Globe in late 1945 or early '46. Typically, it contained an aptly titled "Low Down Blues" on one side and a typical, maudlin ballad, "A Soldier's Return," on the flip.

Clyde Brewer, a multi-instrumentalist and South Texas music legend still active today with the River Road Boys, recalls his professional days with his step-father as formative ones. "I learned a lot of things from him---a lot of things to do and a lot of things not to do," Brewer laughs. "[He'd say], 'When you go out in front of the people, don't overdo it. Always leave them wanting a little bit more.' Now, he'd never do that---he'd follow you out to your car with his fiddle and play as you were driving off---and I'd remind him of it....he'd say, "Don't do as I do, do as I say do."

According to Brewer, Alley exemplified the adage "The Show Must Go On." Even when the band's p.a. system failed, he says, "that didn't stop [him]. He just reached and got him a piece of sheet music and folded it into a megaphone---and got out into the crowd and sang through that."

Nothing daunted Alley and he remained adamant about doing his own material. "We had to play Shelly Lee Alley music at the dances," Brewer recalls. "He might have just written them that morning....He'd put them up on the music stand and just go through' em. We might have to play twenty or thirty to start off with and if someone had a request, he'd say, 'Well, you just have to wait. I've got to do these here first.' And he had a briefcase full of 'em."

After retiring from music, Alley made his living writing lead sheets for would-be songwriters and setting their lyrics to music; he also wrote lead sheets for Floyd Tillman, for Pappy Daily (including leads for George Jone's early sessions), and others. He found it necessary, too, to take a job as a night watchman. "He took his fiddle and his briefcase with him," says Brewer. "He'd sit down in this big warehouse all night long, supposed to be watching everything, writing music." Inevitably, he wrote "Night Watchman's Blues" and once, when a woman who had written a timely poem titled "Prayer Room at the White House" arrived at the job demanding he write music to it immediately, he left her to watch the warehouse, his .45 strapped to her hip, while he went home to compose. (When the prayer room actually turned out to be in the Capitol rather than the White House a disappointed Alley wondered, "What rhymes with Capitol?")

"He was a character. He never meant to be funny," says Shelly Jr. "It just turned out that way."

I'd like to watch the tide come in

And, passing out again,

Take with it these dreams of mine

The things that might have been

---Shelly Lee Alley,

"Broken Dreams"

Music remained Alley's passion to his death. He performed rarely---though he recorded a last disc for Bennie Hess's Jet label and sang "Travellin' Blues" in railroad regalia on Biff Collie's Houston TV show. Mostly, he played for his own satisfaction.

"He'd wear you out," says Shelly Jr. "When I started, I could play a few chords on the mandolin. That's all he needed." It wasn't unusual for him to wake Shelly Jr. at three in the morning to play.

"He'd sing on buses. He'd say 'Let's do "I'll Keep Thinking of You." You sing lead, I'll sing harmony.' And I'd say, 'Daddy, these people don't want---' And he'd say, 'Sing it, boy.' And you had to sing it to shut him up."

His father pushed Shelly Jr. toward a career in music with such single-mindedness that Clyde Brewer would eventually intervened, telling him that the boy needed to learn something besides music. "It got to the point where I had to say, 'Look at you. You've got all that experience and now you're a night watchman. He needs to go to college.' "No,' he says, 'He needs to do what he's got a talent in....I don't care if it's skunk skinner or tail cropper. What you've got a talent in is what you ought to do.' Fortunately, he [Shelly Jr.] got into other things---and got to play a little music, too." Today, Shelly Jr. is a minister at a church in northwest Houston and also plays with the Original River Road Boys.

There were other highlights during those years of retirement: Moon Mullican's excellent, though streamlined version of Shelly's "Broken Dreams" (echoing Satherley a decade before, Moon deemed the song too pop for country audiences as it was written) and the Biff Collie-Little Marge cut of his "Why Are You Blue," for example. Alley wasn't aware of the magnitude of Lefty Frizzell's 1951 hit revival of "Travellin' Blues," however, only of it's local popularity. Nor did he live to see Merle Haggard's 1971 cover, or any of the subsequent fine recordings of it and of "Broken Dreams."

Shelly Lee Alley died in 1964. On April 16, 1994, in the centennial year of his birth, at the Stafford Opera House in Columbus, Texas, Clyde's River Road Boys, Shelly Jr., and Jimmie Rodger's grandson Jimmie Dale Court, among others, presented a program, "From Jimmie Rodgers to Bob Wills: A Tribute to the Music of Shelly Lee Alley," which proved such a success that it became an annual event. In addition, in October 1994, Alley was inducted into the California Western Swing Hall of Fame in Sacramento.

"He used to say he'd written more songs than any man in Texas," Shelly Jr. says with an appreciation that has grown as the years have passed. "Mama got on him years ago. She said he was nothing but a dreamer---dreaming all the time about these record hits." Unfazed, Alley responded typically; he sat down and wrote a song called "If It Hadn't Been for Dreamers."

"He was just as happy playing Carnegie Hall or in a back room," Shelly Jr. concludes. "He was happy just so he could play.

In the early 1820's, Abraham Alley and his brothers joined their Missouri neighbor Stephen F. Austin to form what was known as the "Old 300" Colony in Texas. He settled a few miles south of Columbus on the east side of the Colorado River, and in 1835 married Nancy Millar of another pioneer family. During the Texas War for Independence, he went to the aid of settlers fleeing Santa Anna in the "Runaway Scrape", and his own home was burned. Late in 1836 he returned and built this cabin of oak logs. The Alleys raised two daughters and three sons and often entertained friends and travelers.

Alley Log Cabin in Columbus, TX

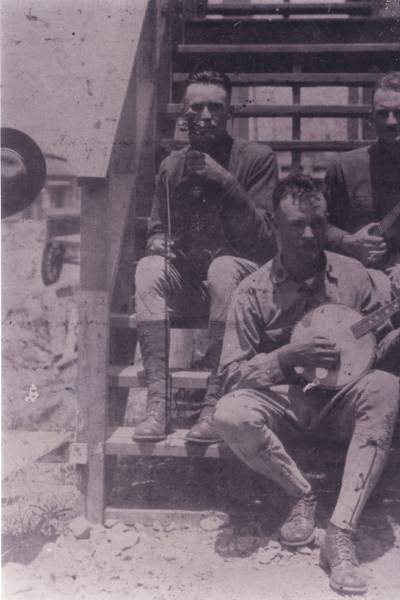

Shelly with sister, Florence and brother, Alvin

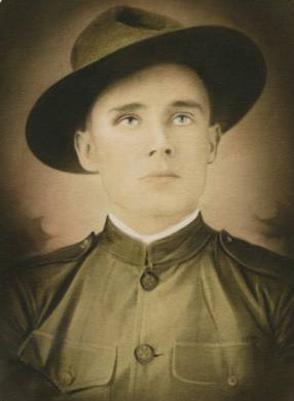

WWI photo of Shelly Lee Alley

Shelly with fiddle in hand at Camp Travis

"Doc" Shelly in sidecar

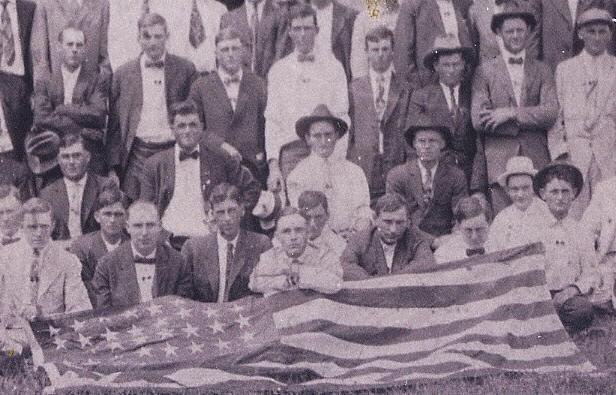

Shelly in front row, center before heading to Camp Travis

Rank: Private - First Class

Unit Staff: Base Hospital

COMPANY: Medical Department Detachment

Maestro Shelly Lee Alley standing by the piano with baton with

the A. Harris (department store) Orchestra, Dallas, mid-1920's

Click play to hear the 1931 recording of "Travelin' Blues" with Jimmie Rodgers

Houston, 1936: Floyd Tillman on resonator guitar, Lew Frisby on bass, and Love Everett on fiddle; Alley's at the far right. The rest we cannot identify.

Shelly Lee Alley: Reluctant Hillbilly

Shelly Lee Alley with stepson "Little Clyde" Brewer walking the streets of Beaumont, Texas in the mid-1940's

Shelly with wife, Velma pregnant with Shelly Jr. walking the streets of Beaumont, Texas in 1945

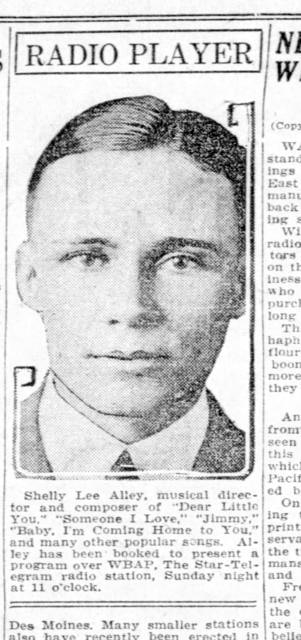

Ft. Worth Star-Telegram

Sunday October 4, 1925

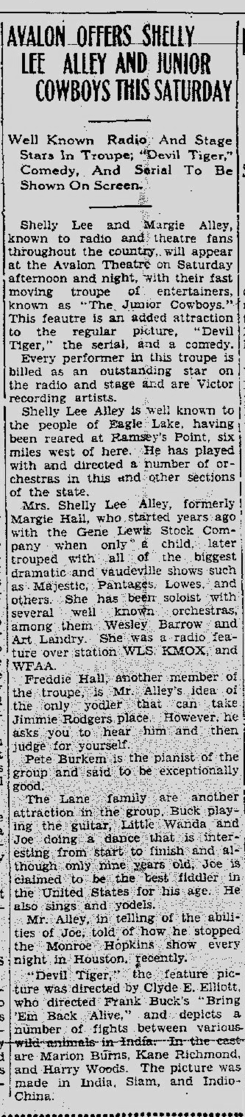

By the summer of 1933, Alley was in Houston leading the original Swift Jewel Cowboys, who were, along with the Bar-Z Cowboys, one of the pioneering groups in the soon-thriving Houston country dance and radio scene. When the group moved to Memphis in 1934, he stayed behind and that summer was touring Texas with his Junior Cowboys, an act that featured his then-wife Margie, a seasoned small-time vaudevillian. (Alley's first marriage had dissolved when his wife demanded he choose between her and music, with inevitable results).

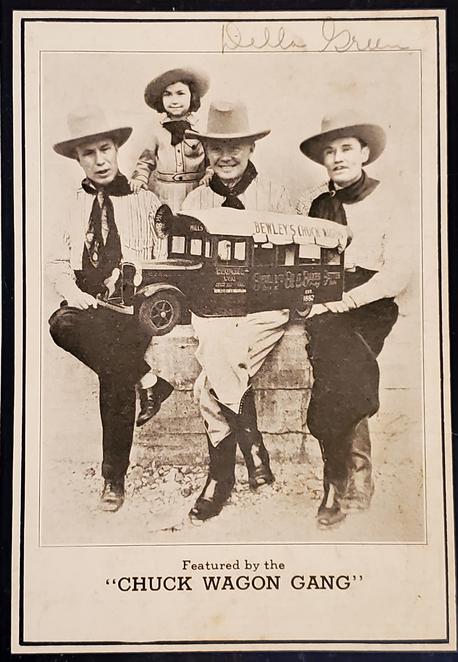

By the following year, Alley was based in Houston once again, advertising flour for Bewley Mills with a short-lived Gulf Coast incarnation of the Chuck Wagon Gang. But the extremely powerful X stations that were springing up at the Mexican border and beaming their signals north soon lured Shelly Lee Alley & his Cowboys (including the well-traveled vocalist/guitarist Curly Perrin and the bassist, future Texas Playboy, and bandleader Rip Ramsey) to Eagle Pass. The move probably brought Alley to the largest audiences he would ever reach. While some, like Cowboy Slim Rinehart, made a killing at the border and lingered for years, Alley apparently wasn't satisfied. He took his XEPN Cowboys back to Houston. A surviving photo of the group shows a very young Floyd Tillman. From there, Alley ventured back to Dallas, where a field trip by A & R man Art Satherley of Brunswick-A.R.C. gave Alley an opportunity to record in June of 1937.

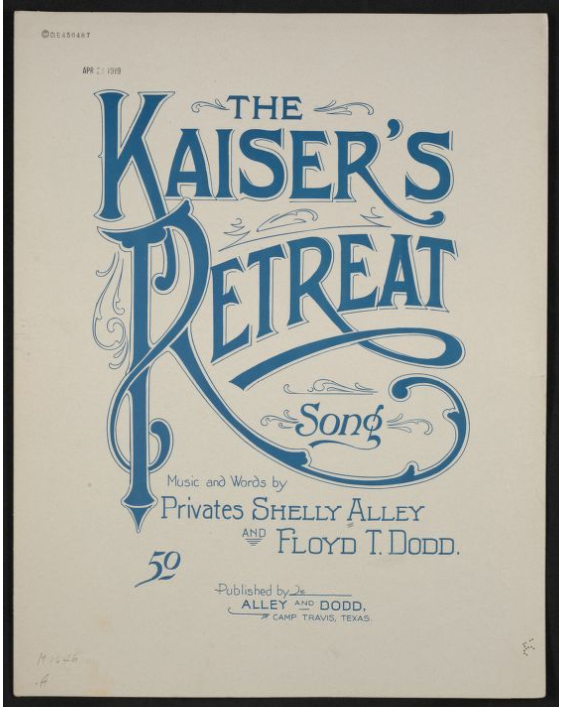

The Kaiser's Retreat Song

by Shelly Alley and Floyd T. Dodd,

Alley and Dodd, c1919.

Courtesy of Library of Congress,

WWI Sheet Music

"Ft. Worth Star-Telegram", Tuesday January 21,1936

"Eagle Lake Headlight", Saturday, August 25, 1934

"Eagle Lake Headlight",

Friday, July 12, 1946

Shelly and Phyllis

Contact: Shelly Lee Alley, Jr.

Email: shellyleealley@hotmail.com

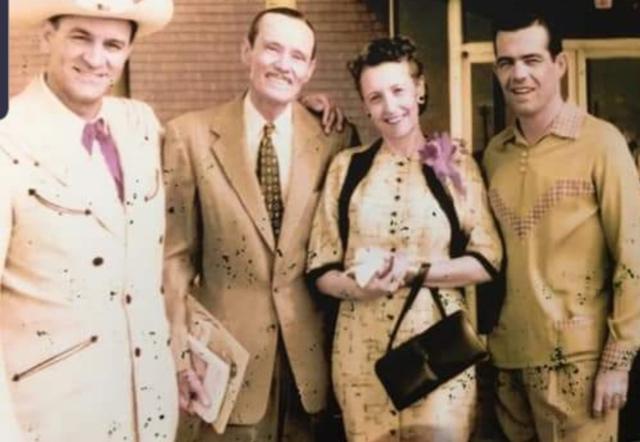

Bennie Hess, Shelly, Mrs. Jimmie Rodgers and Biff Collie

Bennie Hess and Shelly

Swift Jewel Cowboys, Shelly on far right.

Chuck Wagon Gang, Shelly on the right